Nature Physics: how to make multi-component bacterial systems cooperate to form pattern

Recently, the research group of Prof. Jian-Dong Huang in the Hong Kong University and the group of Dr. Julien Tailleur in Université Paris Diderot published in Nature Physics the paper entitled Cooperative pattern formation in multi-component bacterial systems through reciprocal motility regulation. We combined the experimental and theoretical work, showed a general principle for multi-component bacterial system to form pattern through the regulation of motility. The mechanism is spontaneous, without introducing prior coordinates. This research suggests a robust and versatile self-organization pathway in multi-component systems, and is the first time to identify a general mechanism for multi-component active particle systems to form pattern, complementing the known pattern formation mechanisms. The first authors are Dr. Agnese I. Curatolo, Dr. Nan Zhou, and Dr. Yongfeng Zhao. Dr. Adrian Daerr and Prof. Chenli Liu are also the authors of the paper.

We genetically engineered the E. coli strain AMB1655 to construct two populations, labeled by green and red fluorescence respectively. We let each population to constantly express a different signaling molecule, and sense only the signal from the other population. Such particles can sense the density of the other population, and regulate their own behavior, which is often called quorum sensing. Further more, we use quorum sensing system to regulate the expression of CheZ, to enhance or inhibit the motility of the cells.

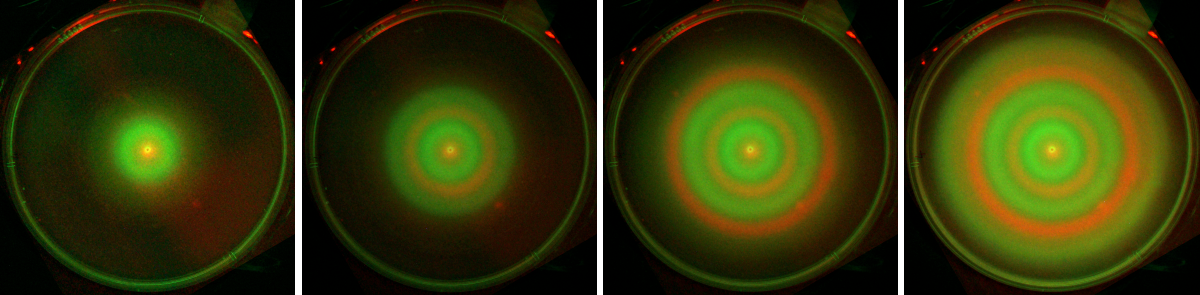

We first use two E. coli populations mutual activating the motility of each other. The two populations do not develop any pattern if cultured alone. But if we mix the two populations and inoculate at the semi-solid agar plate, after one-day cell culture, the colonies of the two populations expand alternatively, and form ring-like segregating pattern. Under fluorescent imaging we find a pattern with alternating green and red rings.

The segregating ring pattern formed by two populations of E. coli with mutual activation of motility (merged channel, time-lapse images).

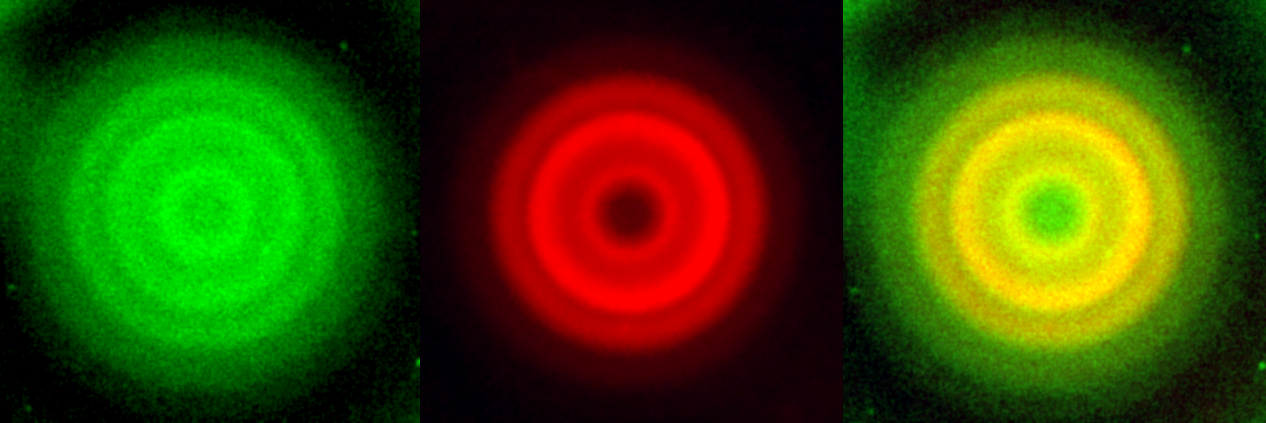

Then we culture two populations of E. coli with mutual inhibition of motility in the same way. After one day they also form ring patterns, but this time they co-localize with each other: the red rings always locate at where the green rings are. Again, we note that the two species do not form pattern when cultured alone.

The co-localizing ring pattern formed by two populations of E. coli with mutual inhibition of motility (red channel, green channel, merged channel).

Why does particles with mutual activation and inhibition of motility can form such different pattern? It can be explained by the particle model. The motion of E. coli can be described as run-and-tumble. Propelled by flagella, cells swim almost straightly. But due to the internal biochemical reactions, they tumble randomly to change their direction of swimming. People have found that this kind of active particles can accumulate at where they swim slower or tumble more frequently, somehow like traffic jam.

Therefore, if one population A can activate the motility of the other population B, and by fluctuations A becomes denser at some region in space, B will be more motile and run out of this region. This then increases the density of B in other regions. Then if B also activates the motility of A, A will also leave where B become denser, and form a positive feedback loop, separating the two populations in space. Oppositely, if A inhibits the motility of B, B will move slower where A is denser, and thus accumulate. If B also inhibits the motility of A, A will also like to accumulate at where B is dense. This is also a positive feedback loop that making the two populations co-localize.

This mechanism only makes two populations to separate or co-localize, but cannot ensure the colony to form stripes or rings with fixed width. This is where the proliferation of bacteria starts to play a role. If in some region of space the bacteria is very dense, they will compete for limited food, which will prevent them from growing and expanding. Then the size of bacterial cluster will be limited and rest the width of the pattern stripe.

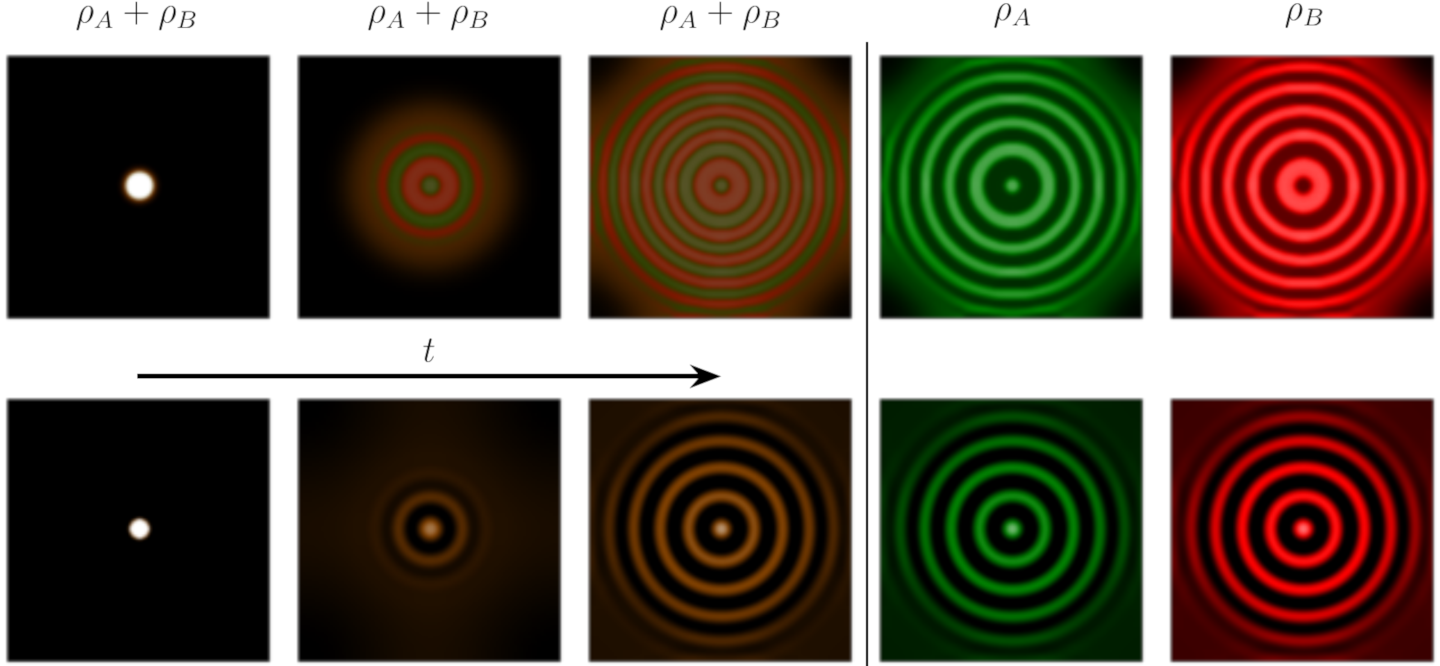

We coarse-grained the particle model, and numerically solved the obtained partial differential equations. We can get the ring patterns that correlated with the experiments. It’s worth noting that if we use the swimming speed, tumbling frequency, and growth rate that have been measured in previous work, the patterns have wave length semi-quantitatively agreed with the experiments. Thus the model well captured the observed experiments.

Simulating the bacteria with mutual activation and mutual inhibition of motility, we get patterns correlated with the experiments.

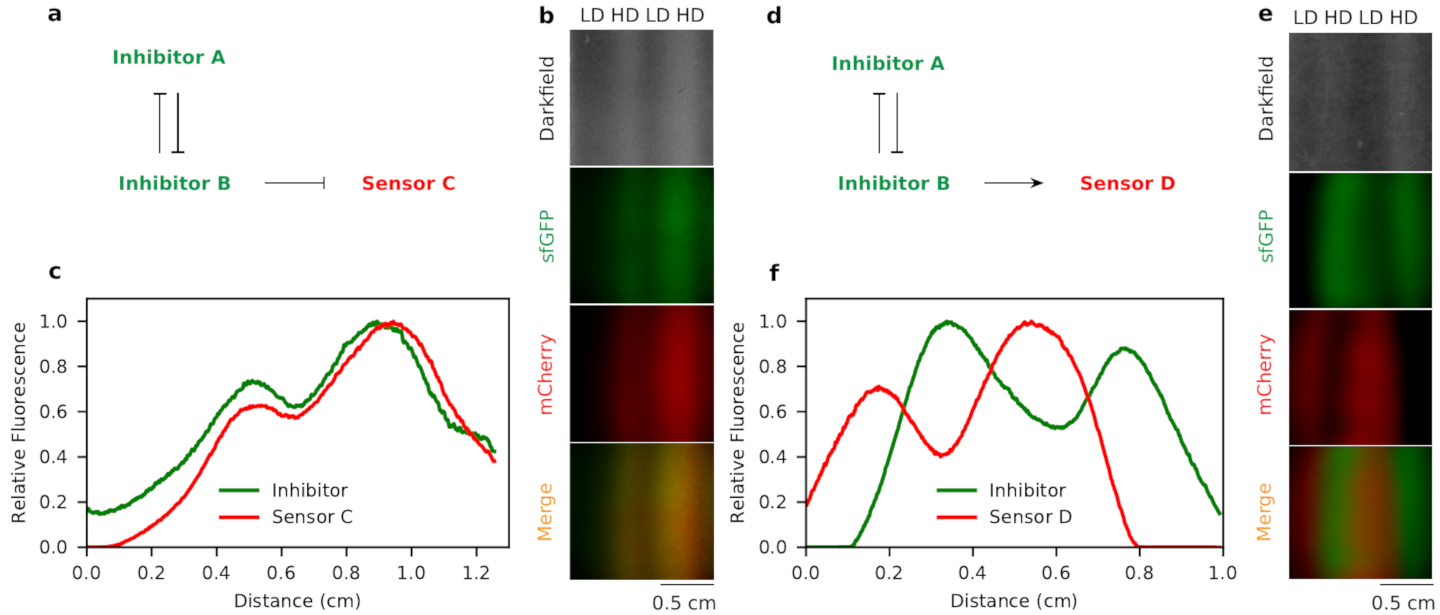

The theoretical model we have built, however, is not only to explain the specific phenomenon of E. coli, but also to provide insights to more generalized systems. We performed linear stability analysis to the partial differential equation model, and found through mutual regulations of motility, the only way to have pattern formation is through mutual activation and mutual inhibition. A naive analogue of Turing’s activator-inhibitor model does not form pattern in regulation of motility. Furthermore, single population which activates its own motility does not form pattern neither. These conclusions have nothing to do with the specific parameters or even the functional forms of the regulations, but depend only on the signs of the derivatives of the regulation function. Thus the model is generic, and the conclusions are all tested in the experiments.

The mechanism can be even generalized into more than two populations interacting. If we know how these populations regulate others’ motility, we are able to predict the patterns formed. As we explained, if population A activates the motility of population B, A will tend to “repel” B. Otherwise if A inhibits the motility of B, it will “attract” B effectively. We can generalize these two rules to, for instance, three populations. If A and B are mutual inhibiting, but both activating the motility of D, then A and B will co-localize and form stripe pattern, and D likes to fill in the places where A and B are not there.

Pattern formed by three populations of E. coli. The populations with mutual inhibition like to stay together, and with mutual activation they like to separate.

The mechanism found in this work is largely different from the known mechanism, such as those based on chemotaxis. It does not require any preexisting positional or orientational cues in microscopic scale or from external signal. The repulsion and attraction in macroscopic cell populations emerge only at collective level. Since we can introduce various networks of interactions and have various patterns, the regulations of motility have a rich potential for applications. It is still an open question if such simple mechanism is already utilized by the nature. But it still provides a robust and versatile tool for engineering and designing self-organization of cells.